What Is Spiritual Grounding: And Why It Is Missing Today

Modern seekers are not lacking practices. They are lacking inner stability. The modern world encourages expansion, more methods, more experiences, more “energy”, but tradition always began with a different question: Is the seeker stable enough to hold what they are invoking? This is why spiritual grounding is not a side-topic. It is the foundation of all inner life. Without it, even sincere practice can magnify restlessness, ego, and confusion.

Spiritual grounding vs emotional comfort

Spiritual grounding refers to the cultivation of inner stability, a state in which the mind, emotions, breath, and sense of self are regulated, contained, and aligned with reality as it is. A grounded person is not free from emotion or challenge, but they are not internally scattered by them. Grounding gives the seeker an inner axis, a steady center from which life is met with clarity rather than reactivity.

This is where many seekers unknowingly drift. They begin to measure spirituality by how they feel, uplifted, emotional, expansive, comforted. But comfort is not a compass. It can come from music, community, affirmation, or even imagination. Grounding is different: it is what remains when the comfort is gone. It is the inner ability to stay coherent, discerning, and steady even when life presses you.

This grounding is important because all genuine spiritual growth depends on stability. Without stability, spiritual energy does not integrate; it amplifies imbalance instead. In traditional systems, grounding was never optional. It was the first requirement before mantra, meditation, ritual, or advanced inner work were introduced.

When a person becomes spiritually “charged”, through intense practices, chanting, visualization, breathwork, or exposure to spiritual ideas, but is not grounded, several things can happen. The mind may become restless or inflated, emotions may intensify without regulation, and the ego may subtly appropriate spiritual language to reinforce identity rather than dissolve it. Instead of peace, there is agitation; instead of clarity, confusion; instead of humility, hidden superiority or dependency.

Common symptoms of being charged but ungrounded include:

- Restlessness after practice instead of quietness

- Irritability, intensity, or sudden pride in one’s “spirituality”

- Emotional flooding (tears, highs/lows) with no real clarity afterward

- Compulsive seeking, needing more methods, more chants, more content

- Strong opinions and identity around spirituality, but weak inner transformation

- The sense of “I am progressing,” while life-patterns remain unchanged

These signs are not proof that the seeker is wrong. They are proof that the foundation is incomplete.

| Feature | Spiritual Grounding | Emotional Comforting |

| Core Goal | Internal Stability & Regulation | Temporary Relief & Soothing |

| Source | Internal Discipline & Sādhana | External Validation & Input |

| Outcome | Long-term Resilience | Short-term Upliftment |

| Feeling | Quiet, steady, and reliable | Expansive, emotional, or intense |

This is especially dangerous when the mind has not been sufficiently cleansed and the seeker engages in practices that are too intense or inappropriate for their current state. An uncleansed mind carries unresolved fears, desires, impressions, and emotional residue.

When spiritual practices are layered on top of this without grounding, those unresolved elements get energized. Fear becomes paranoia, desire becomes obsession, imagination becomes delusion, and discipline becomes rigidity. This is why traditional paths emphasized grounding and purification before power-oriented or inwardly activating practices. Grounding acts as a safety mechanism.

In tradition, this safety principle is simple: no inner power is pursued until steadiness is established. First stability, then intensity. First containment, then expansion. First discipline, then depth.

Emotional comfort, on the other hand, is something very different. Emotional comforting seeks to soothe, reassure, or temporarily relieve discomfort. It often comes through affirmation, validation, inspiration, or emotional release. While emotional comfort has its place, especially in healing or recovery, it is not the same as spirituality, nor is it a substitute for grounding.

Feeling comforted does not mean one is stable. One can feel emotionally uplifted yet remain internally fragile. Emotional comfort often depends on external input: words, experiences, people, or states that make one feel better. When those supports are absent, the instability returns. Grounding, by contrast, builds internal self-regulation. It does not rely on feeling good; it relies on being steady.

This is where many modern seekers become confused. Emotional comfort can feel spiritual because it feels relieving, expansive, or affirming. But spirituality, in its mature form, is not about comfort, it is about capacity. Capacity to hold discomfort without collapse. Capacity to act without agitation. Capacity to know without inflation.

Spiritual grounding is closely tied to emotional maturity. An emotionally mature person does not suppress emotions, but they do not drown in them either. They can experience sadness, fear, joy, or uncertainty without losing discernment or balance. Grounding strengthens this maturity by regulating the nervous system, calming impulsive reactions, and creating a buffer between stimulus and response.

Emotional comforting, when mistaken for spirituality, can actually delay maturity. If every discomfort is immediately soothed rather than understood and regulated, the seeker remains dependent on external reassurance. Over time, this creates a fragile spiritual personality, sensitive but unstable, expressive but unconstrained.

Grounding, by contrast, may feel quiet, even unimpressive. It does not promise immediate relief or emotional highs. What it offers instead is reliability, the ability to remain inwardly coherent across changing circumstances. This is why tradition valued grounding so deeply: because only a grounded seeker can safely deepen practice, receive knowledge without distortion, and walk the spiritual path without losing balance.

In essence, emotional comfort soothes the surface; spiritual grounding stabilizes the core. Comfort may make one feel better for a while. Grounding makes one able to live, practice, and grow without breaking inwardly. That is why grounding is not merely important, it is indispensable.

Why feeling “spiritual” does not equal inner stability

A practical definition of spirituality is this: the movement from a mind-driven life to a truth-driven life, where clarity, responsibility, and inner order replace impulsive reaction.

At its most basic level, being spiritual means orienting one’s life toward truth beyond personal preference, emotion, and self-image. It is the movement from identification with the changing mind toward alignment with what is stable, real, and enduring. In the classical sense, spirituality is not about how one feels, but about how one stands, inwardly, ethically, and existentially.

True spirituality begins when the mind no longer remains in control. The mind is a helpful tool, it can think, analyze, and imagine, but it is also restless and unstable. It moves quickly between desire and fear, hope and doubt. Because of this, when spirituality stays only at the level of the mind, it cannot become steady or lasting. Real spiritual growth does not come from sudden inspiration or emotional highs. It requires discipline, inner maturity, and proper guidance.

This is why traditional spiritual paths never treated spirituality as a personal, self-guided emotional journey. They clearly understood that the mind cannot take itself beyond its own limits. The mind can create strong spiritual experiences, convincing insights, and even stories of awakening. But all of this can happen without any real inner change. Because of this risk, true spirituality required a seeker to become a sādhaka, someone serious, committed, and willing to be shaped slowly over time.

Such maturity cannot develop in isolation. A seeker needs an external stabilizing force: a Guru who is grounded, experienced, and firmly established in the path. The role of the Guru is not to comfort the ego or offer constant praise. Instead, the Guru’s purpose is to expose self-deception and correct inner imbalance. By surrendering to a Guru, the seeker agrees to place their inner life under a higher order than personal likes, dislikes, and emotional impulses. This surrender is not blind obedience. It is a clear and intelligent recognition that real transformation cannot happen within one’s own limitations.

Under the guidance of a Guru, the seeker works on themselves through many demanding processes: discipline, restraint, self-observation, correction, repetition, purification, and the gradual refinement of desire. These processes are often uncomfortable, because they break old identities instead of strengthening them. Yet it is exactly this long-term, guided effort that creates true inner stability. Over time, the mind becomes quieter, life becomes more grounded, and spirituality becomes something lived, not imagined.

Feeling spiritual is mostly an activity of the mind. It comes from emotions, ideas, personal experiences, or self-images that the mind labels as meaningful or elevated. A person may feel open, loving, inspired, peaceful, or “connected.” These feelings can be genuine, but they do not stay. They rise and fall because they belong to the mind. Anything that exists only in the mind has no stable foundation, it appears for a while, changes, and then fades away.

The ego is very skilled at turning these experiences into a spiritual identity. It uses spiritual words, symbols, practices, and stories to strengthen the idea of “I am progressing” or “I am special.” This creates the appearance of growth without real inner change. A person may talk spiritually, behave spiritually, and even inspire others, yet inside they remain fragile. They are still easily shaken by loss, criticism, uncertainty, or unfulfilled desire.

True inner stability does not come from experiences. It comes from inner resolution. It grows when desires slowly reduce, not when they increase. It strengthens when attachment to outcomes becomes weaker, not stronger. As a person becomes less obsessed with gaining and less afraid of losing, fear naturally begins to dissolve. This fearlessness does not arise from confidence, positive thinking, or belief. It comes from inner independence, the ability to remain whole and steady regardless of what life gives or takes away.

This inner independence is deeply dharmic. Dharma is not about appearing moral or socially correct. It is about being aligned inwardly with order and truth. A dharmic person is settled from within. They are no longer torn by small emotional reactions, inner bargaining, or attachment to status, recognition, or possessions. Their actions come from clarity, not compulsion; from responsibility, not insecurity.

This is why stability cannot be created by simply feeling spiritual. It emerges only when a seeker becomes serious about inner growth, when they accept discipline, receive guidance, and slowly let go of the mind’s need to feel special, comforted, or constantly validated. Stability is the result of maturity, and maturity is formed through sustained sādhana under proper direction.

In this sense, spirituality is not a passing mood or a personal identity. It is a deep restructuring of one’s inner life. Spiritual feelings may arise and disappear, but inner stability remains. And it is this stability, quiet, unglamorous, and firm, that shows the presence of true spiritual grounding. It does not seek attention. It does not need constant reassurance. It simply holds, even when circumstances change.

Stability as the Foundation of All Inner Work

All genuine inner work begins with a difficult but necessary realization: without deconditioning, no real foundation can be built. Inner alignment is not something that can be added on top of an already conditioned personality. It requires the slow and deliberate undoing of deeply rooted habits, habits that shape how we see, react, desire, and define ourselves.

These patterns operate silently in the background. They influence emotions, decisions, and identity without being questioned. Until this process of deconditioning begins, spiritual effort remains shallow. It may be sincere and well-intentioned, but it lacks strength. Like a structure built on unstable ground, it cannot support deeper transformation.

True stability arises only when the seeker becomes willing to examine, restrain, and gradually release these inner patterns. This is not a quick process, nor an emotionally comforting one. But without it, no lasting inner work is possible. Stability is not the result of spiritual enthusiasm, it is the result of patient inner reordering.

From the standpoint of Dharma, human consciousness is not empty or neutral. It has been shaped over many lifetimes. Across these lives, impressions called saṁskāras accumulate so deeply that they feel natural and unquestioned. These tendencies automatically pull the mind outward, toward approval and rejection, desire and fear, comparison, gain and loss. Because of this, we learn to understand life mainly through external events and reactions, instead of inner clarity.

This outward pull is not accidental. It is the natural expression of Avaraṇa.

Avaraṇa means “covering.” It refers to the veil that hides reality and replaces it with conditioned perception. Truth is not missing; it is covered. This covering is not just a lack of knowledge or intellectual misunderstanding. It is something lived every day. The mind does not see things as they truly are, it sees them through habits formed over a very long time. Avaraṇa is described as beginningless, not because it cannot end, but because there is no clear starting point in time. Each lifetime inherits this conditioning and adds to it.

This is why many modern seekers feel confused even after years of spiritual practice. Simply using spiritual words, reading sacred texts, or adopting a spiritual identity does not remove Avaraṇa. The covering dissolves only when inner conditioning is faced directly, through discipline, humility, and a life that becomes dharmic from the inside, not just in appearance.

Because of this, Dharma is very clear on one essential point: ignorance is never an excuse for spiritual innocence. A person may not be responsible for how ignorance was acquired, but they are responsible for continuing in it. Claiming purity or spiritual harmlessness while avoiding inner work is itself a form of ignorance. Dharma does not support self-excuses. It demands responsibility, honesty, and the willingness to transform.

Stability is not optional on the spiritual path. Without stability, inner work cannot continue for long. Without inner work, true alignment cannot happen. And without alignment, spirituality turns into imagination rather than lived reality. Stability allows a practitioner to stay present while old patterns slowly loosen. It prevents inner collapse when familiar identities, beliefs, and self-images begin to weaken.

At the heart of this process is the cultivation of equanimity (samatva). Equanimity does not mean becoming emotionally cold or indifferent. It means developing the ability to remain inwardly balanced during pleasure and pain, praise and blame, success and failure. This kind of balance does not appear on its own. It grows through grounding, an inner steadiness that stops the mind from swinging wildly between extremes.

Grounding, however, cannot exist alongside ego inflation. The ego survives by needing to be right, special, justified, or above others. Inner work naturally challenges these habits, which is why resistance arises. Progress requires working with the ego consciously, not by crushing it or fighting it, but by placing it in a larger framework where it can slowly be reshaped.

This is where the role of a spiritual master becomes essential. The Guru provides an external point of stability, someone who exists outside the seeker’s personal conditioning and blind spots. Accepting a Guru is not about becoming dependent. It is about releasing the illusion that one can transform entirely on one’s own. This requires humility, not as a feeling, but as a structure, an honest recognition that deep change needs guidance.

This stage is often compared to preparing for a difficult operation without anesthesia. The ego resists because it senses that it will not remain unchanged. Old identities weaken, justifications fall away, and familiar psychological comforts dissolve. Grounding allows the seeker to stay present through this discomfort instead of escaping into fantasy, denial, or spiritual shortcuts. It is what makes genuine transformation possible.

Ultimately, spiritual grounding happens through one of two inner movements. Either the ego slowly dissolves, or it is redirected into a higher purpose. When the ego is no longer the center of one’s inner life, it loses its power to disturb and destabilize. Whether the ego weakens through clear insight or becomes purified through service, its tight hold begins to loosen. As this happens, awareness naturally becomes quieter and more settled.

For most seekers, the ego does not disappear suddenly. Instead, it is reshaped and redirected. The same energy that once sought attention begins to seek sincerity. The same energy that once wanted control learns to accept discipline. Gradually, personal ambition gives way to commitment to something higher.

When the ego is redirected toward service, service to truth, to the Guru’s guidance, and to dharma, the seeker gains stability without needing intense emotions or dramatic spiritual experiences. Life becomes simpler and more grounded. The seeker is no longer driven by the need to feel special or advanced. Instead, steadiness, humility, and quiet responsibility become the signs of real spiritual progress.

This quiet settling, steady, simple, and often unnoticed, is the true foundation of all inner work. Without it, spiritual effort remains reactive and fragile. With it, the seeker gains the strength to face ignorance honestly, to endure the breaking down of old inner structures, and to mature into a state where clarity is no longer borrowed from experiences. Instead, clarity begins to arise naturally from inner order itself.

In this way, grounding is not just something that supports spirituality. It is the very ground on which all authentic spiritual life is built.

The Vedic View of Spirituality: Inner Order Before Outer Expression

Spirituality as Alignment, Not Escape

True spirituality is not about running away from life. It is about becoming so inwardly aligned that life no longer pulls you off balance. In this sense, spirituality is not escape, it is inner alignment. It is a state where the mind, emotions, actions, and values are no longer in conflict, and the inner world begins to move in one clear direction.

Most people try to understand patterns in the outer world while remaining unsettled inside. But the ability to see life clearly and calmly usually comes only after inner patterns have been resolved. Until then, what we often call “understanding” is simply reaction. We interpret events through unresolved fears, desires, past wounds, and expectations. The world appears confusing not because reality itself is confusing, but because the inner lens through which we see it is disturbed.

As inner patterns slowly come under control through sincere inner work, something natural begins to happen. The seeker starts to withdraw. But this withdrawal is not avoidance. It is not sadness or depression. And it is not escapism. It is a healthy and organic loss of interest in unnecessary noise, external drama, mental restlessness, emotional excess, and the constant need for stimulation.

This is where the modern mind often becomes confused.

When a mind has lived in constant agitation for many years, quietness can feel uncomfortable. Stillness may appear empty or lifeless. Non-reactivity may seem like indifference or withdrawal. So when a seeker begins to step back inwardly, not by force, not through effort, but naturally, the mind becomes uneasy. It labels this change as escape and raises a subtle fear: “Are you running away from life?”

But what is happening is much deeper and far more mature.

The seeker is not escaping life. The seeker is learning to stand at the center of life without being shaken by it. They remain present. They continue to act. They still carry responsibilities and engage with the world. Yet something important has changed inside. The inner urge to react has weakened. Noise no longer demands attention. Thoughts still arise, events still unfold, and emotions still come and go, but now they are seen clearly and allowed to pass without struggle.

From the outside, this can look like withdrawal. The seeker is no longer scattered across every problem. They do not chase every disturbance. They do not argue internally with every situation. They stop feeding the mind’s constant need to control and interfere. To an observer, this may look like disinterest or detachment. But from within, it is the opposite of escape, it is deep presence.

It is being fully involved in life while remaining inwardly untouched.

The mind struggles to understand this because it is familiar with only two ways of functioning:

- reacting and becoming disturbed, or

- avoiding and suppressing.

When the seeker enters a third way, stable witnessing with full participation, the mind tries to fit it into old categories and calls it “escape.” But this is not avoidance. It is mastery. It is the rise of a centered awareness that no longer needs agitation to feel alive or important.

This is why a truly spiritual person often appears calm in situations where others feel trapped, pressured, or emotionally overwhelmed. This calmness does not come from ignoring reality or disconnecting from life. It comes from being aligned with reality. What may look like “nothing is happening” on the outside is actually something very deep happening within: the inner world has stopped negotiating with every external pressure.

This is the key point: being spiritual means facing life with ease.

Not because life becomes easy, but because the inner person becomes stable. Challenges may still exist, but they are no longer experienced as threats to identity. Difficult situations still arise, but they do not disturb the mind deeply. Losses may still occur, but they do not collapse the sense of self. The spiritual person moves through life with a quiet intelligence, as if life never truly corners them.

At this stage, it is very common for a seeker to ask, “Am I escaping?”, especially when the world around them feels frantic, demanding, and restless. But the more truthful answer is usually this:

No. You are not escaping. You are aligning.

Escape is driven by fear. Alignment is guided by clarity. Escape avoids reality. Alignment meets reality without being inwardly shaken. Escape is unconscious running. Alignment is conscious steadiness. Once this steadiness is established, spirituality stops being something one does and becomes something one is, silent, stable, and deeply free.

The Vedic Emphasis on Steadiness (Sthiti) and Regulation (Samyama)

The Vedic tradition is not merely offering moral advice or personal guidance. It is describing a cosmic psychology. The same principles that govern the universe also govern the inner world of a human being. That is why stability and restraint are not optional personal traits, they are spiritual laws.

A powerful verse from the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam expresses this clearly:

एवं प्रवर्तते सर्गः स्थितिः संयम एव च ।

गुणव्यतिकराद् राजन् मायया परमात्मनः ॥

“O King, in this way creation (sarga), steadiness (sthiti), and regulation or restraint (samyama) all operate

through the interaction of the guṇas, by the divine power (Māyā) of the Supreme Self (Paramātmā).”

How This Verse Explains Grounding and Equanimity

This verse reveals something very important.

It does not say that only creation (sarga) happens through Māyā. It also includes:

- Sthiti , stability, maintenance, inner holding

- Samyama , regulation, restraint, disciplined control

This means that inner steadiness is not a personal achievement alone. It is part of the same cosmic order that governs the universe. The same divine power that moves galaxies also governs the balance of the mind.

When the guṇas mix chaotically, the mind becomes restless, fearful, reactive, and scattered. But when the guṇas become regulated, sthiti and samyama naturally arise. This is what true grounding looks like.

In simple terms, “sthiti + samyama” describes a protected and stable mind. When this happens:

- the aura becomes fortified

- the mind becomes disciplined

- overthinking reduces

- courage returns

- emotional turbulence settles

This is equanimity, not numbness, not suppression, but deep inner order. And this inner order is the true mark of spiritual grounding.

This verse gives a complete Vedic summary of true spiritual grounding:

- Sthiti means your inner center does not shake. You remain grounded, stable, and steady even when life is uncertain.

- Samyama means your energy does not leak. Your prāṇa is regulated, your senses are disciplined, and your inner power is no longer wasted through restlessness, anxiety, or impulse.

When sthiti and samyama arise together, the natural result is samatā, equanimity. You stop swinging between emotional extremes. Even in intense situations, you remain calm, clear, and balanced.

Why This Is Not “Your Effort Alone”

The verse clearly states that these processes happen “by the Māyā of Paramātmā.”

This means that while the seeker must practice sādhana, the deeper transformation is not produced by ego-driven control. It is not something the mind forces into existence. Instead, it happens when grace and cosmic order begin to reorganize the inner guṇas.

This fits perfectly with an essential Vedic understanding:

A mantra is not just a sound. It is a living spiritual force. Its purpose is to stabilize the mind, regulate prāṇa, and protect the subtle body by restoring inner order.

Because of this, the Vedic tradition repeatedly praises sthiti (steadiness) and samyama (regulation). Together, they form the true foundation of grounding and equanimity. This verse reminds us that not only creation (sarga), but also the stability and restraint of the mind operate through the interplay of the guṇas, guided by the divine power of Paramātmā.

When the guṇas are disturbed, the mind becomes reactive, fearful, and easily shaken. But when the guṇas are purified and regulated through steady sādhana, something natural happens. Sthiti arises, the inner center stops trembling. Samyama strengthens, prāṇa no longer leaks through anxiety and agitation.

This is exactly what we described earlier. Through sustained practice, the mantra gradually fortifies the aura, quiets mental turbulence, and creates a calm, protected steadiness. The seeker begins to move through life with samatā, equanimity, instead of emotional extremes.

Why Ancient Paths Began with Containment, Not Expansion

Ancient spiritual paths understood something that modern seekers often miss: before consciousness can expand, it must first be contained. Expansion without containment does not bring freedom. It leads to fragmentation and instability.

The sages saw that the real human problem was not a lack of experiences, power, or expression. It was the absence of inner control. In this state, the Self becomes quietly trapped by its own unregulated tendencies.

Desire plays a central role in this imprisonment. Each desire acts like an unnecessary handle sticking out of the ego, something the outside world can easily grab. Over time, the ego becomes covered with these handles: ambitions, cravings, fears, suppressed emotions, and unmet expectations.

Nature, or Māyā, does not need to overpower us directly. It simply pulls on these handles, and we move.

Because of this, we believe we are choosing freely. We think we are deciding, acting, and exercising control. But in reality, we are being handled. Situations, people, praise, blame, success, and loss all gain power over us through these exposed desires.

This is the great paradox of Māyā. The very mechanism that binds us also convinces us that we are free. The more reactive and desire-driven we become, the more we feel we are exercising choice, while remaining deeply controlled from within.

This illusion leaves us deeply vulnerable. When life changes suddenly, when something breaks, relationships strain, ambitions fail, or even succeed too strongly, we feel shaken at the core. We try to fix one problem and end up creating several more. Because our desires are unchecked, our ambitions are not examined, and our emotional residues remain unresolved, we stay open to being pulled by external forces. Situations, systems, people, events, and even our own thoughts gain power over us.

The scriptures point to this condition again and again. They do not accuse the world of being cruel or unfair. Instead, they reveal the hidden structure through which we give away our inner authority. The real tragedy is not that Māyā acts upon us, but that we unknowingly cooperate with it.

This is where the Guru enters, not as someone who offers comfort, but as someone who points clearly. The Guru points toward the Moon: the light of Truth, the unchanging reality beyond the mind and beyond circumstances. But our vision is narrow and our attention restless. Instead of looking at the Moon, we focus on the tree that blocks our view, or worse, on a single leaf. We analyze the leaf, argue about it, admire it, or criticize it, and in doing so, we completely miss what is being shown.

Because of this, the Guru’s instructions often feel repetitive, limiting, or even frustrating. They ask us to stop reaching outward. To a mind trained to acquire, collect, and react, this feels unnatural. Yet the scriptures insist on containment for one clear reason: containment alone leads to contentment. As long as desire remains sharp and unchecked, peace cannot be known, not because peace is absent, but because the ego keeps giving it away.

It is the ego, not fate, that hands over our peace. It trades joy for approval, stability for excitement, and clarity for control. Through its many forms, thought, imagination, memory, and projection, the mind becomes a busy marketplace where peace is exchanged again and again. Life after life, this trade continues. We may experience moments of pleasure or success, yet remain inwardly restless, unsettled, and strangely unfulfilled.

This is why ancient spiritual paths did not begin by asking, “How can I expand?” They began by asking, “Where am I leaking?” The focus was on sealing the cracks through discipline, restraint, repetition, and inner rigor. Not to deny life, but to stop losing the Self.

The scriptures are also very honest about pain. Pain cannot be avoided. Karma must unfold, and lessons must be learned. But suffering is optional. Suffering arises when pain meets resistance, attachment, and uncontrolled desire. When we learn to contain ourselves, when we remove the handles that Māyā pulls, we may still feel pain, but we no longer collapse into suffering.

This is the quiet wisdom of the ancient approach. Through steady spiritual discipline, through containment of desire, and through humility before the Guru and the scriptures, the seeker slowly regains inner agency. Peace is no longer borrowed from circumstances. Joy is no longer dependent on outcomes. Stability becomes something that arises from within.

Only when inner containment is established does true expansion become possible. This is not the expansion of experiences, powers, or emotional highs, but the expansion of freedom. And this is exactly what the scriptures have always pointed toward.

When containment is lost, spirituality slowly turns into performance. Practices become displays. Words become signals of belonging. And when performance becomes central, religion easily turns into identity, something we show, defend, and emotionally attach ourselves to, rather than a discipline that reshapes the inner life. This is where the modern drift begins.

Religion vs. Spirituality in the Modern World: Where the Drift Began

When Religion Became Identity Instead of Discipline

The original purpose of religion was never to create an identity. It was meant to transform the human being. Religion existed to make a person inwardly stable, ethically aligned, and capable of seeing truth beyond ego, impulse, and habit. It was designed as a structured discipline, to ground the mind, regulate desire, refine intelligence, and gradually awaken clarity and dispassion.

When religion performs this role, it becomes a bridge to true spirituality. When it fails to do so, it becomes only a label. People may belong to it, defend it, or display it, but it no longer transforms them from within.

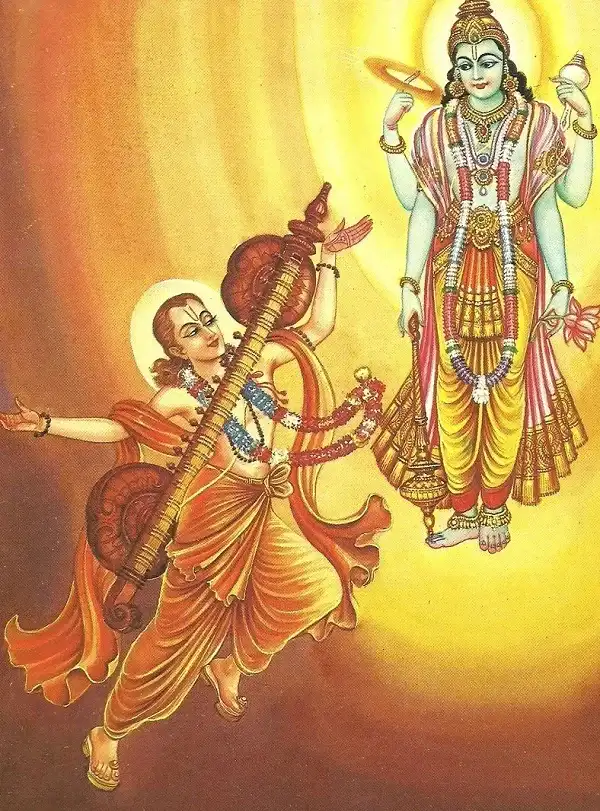

The Śrīmad Bhāgavatam opens with a powerful and symbolic story that reveals this truth in a way that feels strikingly relevant even today. The sage Śrī Nārada, deeply concerned about the state of the world, seeks to understand the condition of Bhakti Devi, the personification of devotion. In his vision, Bhakti Devi is seen traveling from the southern regions of India toward the north, accompanied by her two sons, Jñāna (Knowledge) and Vairāgya (Dispassion).

This opening image quietly points to a deeper problem: devotion may continue to exist, but without knowledge and dispassion, it becomes weak, confused, or sentimental. True spirituality requires all three to grow together. When discipline weakens and identity takes over, devotion loses its grounding, and the drift begins.

As the three travel northward, something troubling takes place. Bhakti Devi remains present, but her two sons slowly weaken. Jñāna (Knowledge) and Vairāgya (Dispassion) grow old, frail, and ineffective. By the time they reach the northern regions, they are so exhausted that they lie dormant, almost lifeless. When they finally arrive in Vṛndāvana, the eternal abode of Lord Krishna, something extraordinary happens. Bhakti Devi immediately regains her youthful radiance. Yet Jñāna and Vairāgya remain asleep, too weakened to awaken easily.

This story is not only about geography. It is a civilizational and psychological allegory. It offers a timeless warning: devotion without knowledge and dispassion cannot sustain real transformation.

In the modern world, devotion appears strong on the surface. We see grand festivals, crowded temples, pilgrimages, discourses, chanting, retellings of the Lord’s pastimes, and a strong sense of religious belonging. Yet despite this visible devotion, society does not show a matching depth of inner change. Clear thinking does not consistently improve. Ethical clarity does not automatically deepen. Emotional maturity does not reliably appear. The same patterns, greed, fear, conflict, attachment, insecurity, repeat generation after generation.

Why does this happen?

The answer lies in Śrī Nārada’s vision.

Religion has slowly shifted from being a discipline to becoming an identity. People identify as devotees, believers, or followers of a tradition, but the inner disciplines that awaken Jñāna and Vairāgya are often neglected. Knowledge is reduced to information or scripture quoting. Dispassion is misunderstood as withdrawal or ignored altogether. Devotion becomes emotional, expressive, or cultural, but not transformative.

A religious identity can give comfort, belonging, and social harmony, and there is nothing wrong with that. But when identity replaces inner work, religion loses its deeper power. It becomes something we are, not something that shapes us. We defend it, display it, and emotionally invest in it, while our inner life remains mostly unchanged.

Without Jñāna, devotion lacks discrimination. A person cannot clearly see patterns in their own life, recognize repeated karmic cycles, or separate what is essential from what is merely attractive. Without Vairāgya, devotion stays tied to desire, the desire for reward, recognition, safety, or emotional comfort. When both knowledge and dispassion are weak, the seeker remains sincere but unfree, devoted yet inwardly bound.

This is the condition the allegory warns us about, and invites us to correct.

This is why the Bhāgavatam places such strong emphasis on restoring Jñāna (Knowledge) and Vairāgya (Dispassion) alongside Bhakti (Devotion). Devotion by itself can inspire the heart, but it cannot liberate a person unless it is supported by clarity and detachment. Bhakti becomes truly powerful only when it disciplines the ego instead of decorating it.

Today, many people live mainly through their religious identity. They are deeply concerned about its recognition, its honor, and its survival. Yet their inner life remains largely unchanged. The same fears continue. The same attachments rule decisions. The same emotional ups and downs govern behavior. And the same cycles of suffering repeat. This leads to an honest question: what is the value of religious identity if the inner person does not change?

The relevance of Śrī Nārada’s vision is impossible to miss. Bhakti has not vanished, it has simply been separated from its stabilizing companions. The confusion and unrest we see today are not due to a lack of religion, but due to religion that has lost its disciplinary core.

True religion does not ask, “What do you identify as?”

It asks, “What has changed within you?”

When religion functions as discipline, it grounds the seeker, sharpens intelligence, and slowly cultivates dispassion. When it functions only as identity, it creates emotional attachment without inner growth. The Bhāgavatam’s message is clear: without the awakening of Jñāna and Vairāgya, even devotion remains incomplete.

To restore religion to its rightful place, we must return it to its original purpose, not to make us believers, but to make us free, stable, and inwardly transformed human beings.

A seeker does not need more spiritual stimulation. A seeker needs ground. When grounding returns, emotional maturity returns. When maturity returns, discipline becomes natural. And when discipline becomes natural, spirituality stops being a temporary feeling and becomes a way of living, quiet, steady, and deeply transformative.

How to Begin Spiritual Grounding with a Simple Mantra Practice (3 Simple Steps)

Step 1: Prepare the Inner and Outer Space , 1 minute

- Sit comfortably in a clean, quiet place where you will not be disturbed.

- If you have a Yantra or Deity image, place it before you. If not, simply sit with the spine gently erect.

- Take one slow, deep breath and consciously allow the body and mind to settle. Let the intention be steadiness, not experience.

Step 2: Mantra Grounding , 2 minutes

- Gently chant a grounding mantra of your choice, or simply repeat the mantra given to you by your Guru.

- Chant slowly 11 or 21 times, allowing the sound to pass through the body without force.

- Let the mantra stabilize the breath, calm the nervous system, and create an inner sense of containment.

Step 3: Silent Settling , 2 minutes

- After chanting, sit quietly for a few moments.

- Do not analyze or expect anything. Simply remain present and observe the mind without engagement.

- End the practice with a brief sense of gratitude and return to daily activity without haste.

Viraja Devi Dasi

Rohini Devi Dasi